On the occasion of the Festiwall 2019, I had dedicated a post to the fresco of Ardif to say all the good I thought of this young artist. His fresco of the Oberkampf Wall arouses a great deal of interest and highlights Ardif’s singular talent.

It represents a dragon and occupies almost all the space of the billboard made available to the association the M.U.R. by the borough council (4x3m). The species of flying dragons is composed of many subspecies: the dragon painted by Ardif is, shall we say, Asian (it is not necessary to go into detail of the differences between Tibetan, Chinese and Japanese dragons). Let’s say that this dragon is Tibetan since the artist dedicates his work to Tibet (Art for Tibet). It deploys its long serpentiform body along the entire length of the wall. On the model of the mechanimals, appear as a skinned internal organ of the dragon made of mechanical parts and ancient architectures. The dragon is painted black and white except the iris of the eye painted blue.

Since the Man paints, he painted animals. It is therefore not their representation that distinguishes Ardif from other artists. Although the precision of the stroke and the quality of the execution is quite remarkable. The originality of Ardif’s artistic project, which he calls the mechanimals, an ardifian neologism formed by the contraction of mechanics and animals, is the combination of animal painting and “technical drawing”.

Not being able to say everything about Ardif’s art, I will focus on what I think is most innovative, the mixture of mechanics and architecture that is supposed to be the dragon’s bowels.

An Innovative artist, I use the word against the odds, because this curious mixture refers to an aesthetic from the second half of the 19th century. Let’s dwell for a moment on what I called “technical drawing.” Of course, it is an image because the work is completely painted. But the line by its precision evokes industrial design. In a recent interview, Ardif refers to it: “Learning to draw technically has influenced my way of doing, through the use of fine felt, Rotring. I often start with a pencil that is coarse enough for the composition, before drawing the animal. These tools allow working the textures, feathers, furs, or scales, which will then influence the work on the mechanical part and the objects that will compose it”. The artist is indeed the son of an architect and he studied architecture!

In his fresco of the Dragon, Ardif added only one touch of colour, the blue of the eye. If we look at the whole of his production, the collages and frescoes, the least we can say is that the painter uses colour with relative parsimony, at least for the mechanical part of the animals. This trait reinforces the kinship with the technical drawing. Besides, the use of greys, blacks of different densities and whites more or less pure reinforces the contrast with the “physical” part of the animal. Ardif rightly insists on this point: “Black and white is a base that I like very much, even if from time to time I enhance it with colours because there are animals whose hue directly evokes something, whether it is the pink of the flamingo or the colour fox redhead. This marks an even more marked contrast with the machine and brings a novelty. »

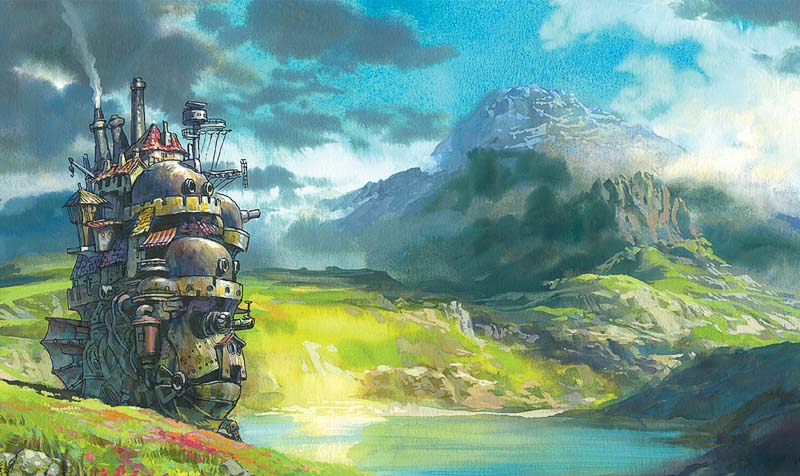

The mechanical elements evoke an ancient time, that of the Industrial Revolution, of the steam engine, to situate it approximately the second half of the nineteenth century, roughly the Second Empire. The mechanics are not only that of another time, but it is also aged in its appearance. Ardif could represent superb copper or brass gears, combined with steel gables, black with blue reflections. Others have done it before him. He gives his old mechanics the patina of the passing of time. It is not the brilliance of metals that interests him but much more the reference to aesthetic. The artist “quotes his sources” in an interview: “It’s a cultural influence that comes from the films I loved, like Star Wars, which represent an aged, dented and underground future. Art, like the city, must have a patina, strata. The technology I draw could not be Apple, it is an open-mechanism technology, which shows the circuit boards. Technology is first and foremost a mechanic, a production line. It’s the same in architecture: I prefer raw concrete to a matted concrete, raw wood to smooth and varnished wood, rusty metal to polished metal. Steampunk is the culture of Jules Verne and Hayao Miyazaki: flying machines are not a match! In this, “The travelling castle”, with its improbable but coherent architecture, is a fantasy. »

What about steampunk? A definition of this literary current is probably necessary: “This is a euchronia referring to the massive use of steam engines at the beginning of the industrial revolution and then in the Victorian era. The term “steampunk” is a term coined to describe a genre of literature born at the end of the 20th century. The term was coined in the late 1980s as a reference to cyberpunk (a term that appeared in 1984). The influence of steampunk literature was certainly decisive in the implementation of Ardif’s artistic project, but I have the weakness to think that the illustrations of Jules Verne’s novels and in particular those of the Herschel collection played a role essential in its representational choices (use of black and white, “futuristic” design of machines and vehicles, etc.).

I admit to being sensitive to this aesthetic and this for very personal reasons. I was fascinated by the 10 Baltard pavilions in the “Halles de Paris”, with the architecture of Eiffel Iron. The memory of my discovery of the Museum of Arts and Crafts, a little over a half-century ago, remains a very much tinged moment with joy and mystery.

Today, the museum’s metro station reflects this aesthetic; a red copper station transformed into Nautilus, with its windows and giant gears. When I was 10, I wanted to be a locomotive driver. They were monstrous, huge, stifling jets of steam and boiling water, their steel wheels squealing on the rails in a firework of sparks. I wish I’d driven them like Ben-Hur’s tank! They were “human beasts” as Ardif’s animals are “machine animals”.

Written by : Richard Tassart